Evidence from mummified remains of three children discovered atop an Argentinian volcano suggests they were drunk and stoned for a year leading up to their ritual sacrifice.

Three Inca children found mummified in a shrine near the peak of a 6,700-meter Argentinian volcano consumed vast quantities of corn alcohol and coca, the plant from which cocaine is derived, for a year before they were sacrificed as part of their society’s religious practices. The children, a 13-year-old girl known as the “Ice Maiden” and a boy and a girl between the ages of 4 and 5, were likely sedated to keep them compliant in the death ritual, according to the authors of an analysis of the mummies published Monday (July 29) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

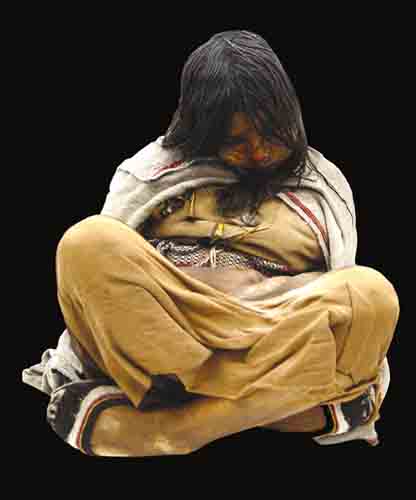

The Ice Maiden, a mummified 13-year-old girl discovered in a shrine atop an Argentinian volcano

well-preserved samples ever discovered, mostly due to the frigid conditions of the high altitude tomb in which they were found in 1999. (See "Pneu-mummy-a" from the November 2012 issue of The Scientist for a story of previous research done on the remains.)

Pneu-mummy-a

Comparing the protein profile of a 500-year-old Inca mummy to modern humans reveals an active lung infection prior to sacrifice.

MINI MAIDEN: This little girl (La Nina del Rayo) died at age 6 and was preserved remarkably well by the Andean conditions.

Examination of three frozen bodies, a 13-y-old girl and a girl and boy aged 4 to 5 y, separately entombed near the Andean summit of Volcán Llullaillaco, Argentina, sheds new light on human sacrifice as a central part of the Imperial Inca capacocha rite, described by chroniclers writing after the Spanish conquest. The high-resolution diachronic data presented here, obtained directly from scalp hair, implies escalating coca and alcohol ingestion in the lead-up to death. These data, combined with archaeological and radiological evidence, deepen our understanding of the circumstances and context of final placement on the mountain top. We argue that the individuals were treated differently according to their age, status, and ritual role. Finally, we relate our findings to questions of consent, coercion, and/or compliance, and the controversial issues of ideological justification and strategies of social control and political legitimation pursued by the expansionist Inca state before European contact.

In 1999, high in the bone-dry plains of the Atacama Desert in Argentina, Johan Reinhard, currently the Explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society, and colleagues uncovered three exceptionally well-preserved corpses. Two children, a girl and a boy aged 6 and 7 respectively, and a 15-year old adolescent they named “the Maiden” had all been sacrificed some 500 years ago and buried near the summit of one of the world’s highest volcanoes, Llullaillaco.

The conditions of preservation in the high Andes were so unique that to prepare the mummies for display in Salta, Argentina, curators there consulted forensic anthropologist Angelique Corthals, then at the American Museum of Natural History, to recreate the extreme cold and dryness required to keep the bodies looking fresh and to preserve their tissues and organs for further study. Five years later, in 2009, after the mummies had eventually gone on display, Corthals revisited the museum to check on their condition.

She sampled sputum (mucus coughed up from the lower airways) from the mummies to test whether they had been sedated before their sacrifice, likely with a kind of corn liquor. Corthals also sampled a bloodstained portion of cloth found near the 7-year-old boy’s mouth. She used proteomics to map the proteins in the blood sample to determine where in the body the blood had come from, since different sets of proteins are found in the gut compared to the lungs, for example. When Corthals saw the blood profile, she began to realize just how rich in information it was.

“We never expected we would have such a slew of proteins coming out of the sample. We couldn’t believe the result,” says Corthals. It was so amazing, they ran it again, and got the same bounty of proteins. “We realized the proteins were better preserved than we thought they would be, and we ran very accurate mass spectrometry, which gave us this amazing profile.”

The success of the method, called shotgun proteomics, allowed Corthals and the team to answer deeper questions about the mummies. In previous CT scans they had noticed that the eldest mummy, the Maiden, had lesions on her lungs that could indicate infection. They could even see streaks of mucus under both nostrils.

Researchers had previously detected pathogens in ancient samples using DNA analysis, but linking the presence of microbes to a disease state is tricky because some bacteria, for example Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can persist in an individual for a prolonged time period without causing active infections. Detecting the immune response of a host, which indicates an active infection, is also possible, but requires the use of antibody-binding immunoassays, which are prone to false positives and negatives when used on archaeological samples.

This work proves that modern instrumentations and techniques are capable of minimizing the guesswork

in forensic and historical sampling.

—Mehdi Moini, Museum Conservation Institute at the Smithsonian Institution

Corthals compared the Maiden’s extensive protein profile to a database containing 87,061 human protein sequences, and found elevated levels of proteins associated with immune response to inflammation of the lungs, similar to those seen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and mycobacterial infection.

The team used the boy’s protein profile as a control, since he showed no signs of infection in CT scans and radiology analysis (the blood on the cloth was deemed the result of trauma) and had likely undergone a similar amount of protein degradation. The Maiden’s inflammatory and immune-response proteins were elevated compared to the boy’s, while all other protein levels were comparable.

Mehdi Moini of the Museum Conservation Institute at the Smithsonian Institution, who has recently demonstrated the use of proteomics in dating archaeological samples, says Corthals’s work is “yet another fine example of the application of modern mass spectrometry and proteomics technologies to anthropology and museum specimens.” He says that this new approach “not only shows the presence of the pathogen, it also demonstrated that the pathogen actually produced an active infection.”

As well as corroborating the evidence from CT scans and radiology analysis, Corthals’s team constructed the DNA profile of the samples to probe what pathogen was responsible. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the most likely culprit as part of the pathogenic Mycobacterium avium-bovis-tuberculosis complex.

“This work proves that modern instrumentations and techniques are capable of minimizing the guesswork in forensic and historical sampling,” says Moini. While 500-year-old mummies were used in this case, Corthals, now at the City University of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is enthused about myriad potential applications and has already been swamped by e-mail requests for new collaborations. “I’m not going to stop at ancient remains,” she says. “One of the interesting things would be to work on the frozen bodies that were preserved with the flu virus from the Spanish flu and see whether we can say anything about the immune system of these people that died from the flu.”

Currently, Corthals is working with a team from Brussels University in the “Valley of the Nobles” outside Luxor, Egypt, where she is uncovering 3 millennia of human activity, from high-ranking nobles who lived around 1400 BC to Napoleonic soldiers who were ambushed in the region and had their bodies dumped in one of the Valley’s tombs at the beginning of the 19th century. Corthals set up the first ancient-DNA lab in Egypt to try to use genetic analysis to identify the missing mummy of Queen Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most powerful rulers.

Proteomics could now help solve some of ancient Egypt’s most captivating mysteries, such as what really killed the boy king Tutankhamen. “It would be nice, but it would be more challenging, because King Tut’s mummy is more damaged, so I don’t know what kind of profile we would get,” Corthals says. “But it would be very interesting to see even a partial profile.”

Detailed biochemical analysis of the mummies’ hair provided a record of what substances were circulating in the blood as new hair cells formed. Led by forensic archaeologist Andrew Wilson of the University of Bradford in the U.K., researchers discovered that the children ingested alcohol and cocaine for about a year before their death, and that consumption spiked dramatically in the weeks before they were killed.

Wilson and colleagues suspect the children were marched from the Inca capital of Cuzco to the volcano, Llullaillaco, stopping along the way to consume massive amounts of alcohol and coca in village ceremonies. The Ice Maiden, whose body was discovered cross-legged and slumped slightly forward as if she was sleeping at the time of her death, was also found with a large wad of chewed coca leaves in her mouth.

A previous analysis by Wilson’s group revealed a marked improvement in the nutritional content of the children’s diet in the year before their death, indicating they were well cared for in preparation for the sacrifice ceremony. Also, in the current study, scans of the Ice Maiden’s body suggested she died on a full stomach and had not recently defecated. “To my mind, that suggests she was not in a state of distress at the point at which she died,” Wilson told LiveScience.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.