IS 112 OCEAN AVENUE REALLY HAUNTED?

Crime Scene Photographs at the bottom of this page

On December 18, 1975, more than a year after the terrible murders, a family of five moved in. They were George and Kathy Lutz and their children Daniel, 9, Christopher, 7 and Missy 5. Twenty-eight days later the family fled the house, claiming it was haunted.

The Amityville murders - Removing

the bodies

According to the Lutzes and their priest, terrible events occurred. The Lutz family fled in fright, never to return.

One of the paranormal activites that the Lutz's claimed to have seen was a white-hooded figure, its face half-blasted away as if by a gun, which appeared in the living room fireplace and was permanently burned into the fireplace wall.

Ronald DeFeo, Sr.,

victim

Many authorities have since then publically stated that the hauntings were a hoax, and other families have since lived in the house without incident.

In fact, on March 18, 1977, Jim and Barbara Cromarty bought 112 Ocean Avenue for $55,000, way below the value of the house. Because of the notoriety that befell the house, the Cromartys legally changed the address to 108 Ocean Avenue to ward off thrill seekers. The Cromartys also added a fake window to the front of the house. On August 17, 1987, Peter and Jeanne O'Neill purchased 108 Ocean Avenue for an unspecified amount, and lived there happily until 1997. Other than the Lutzes, no other family who lived at 112 Ocean Avenue encountered paranormal activity. The house is still standing, but the eye-like windows that used to glow red at night have been replaced with more modern looking windows.

But what if the Lutz family was right? What if the tragic DeFeo children couldn't find their way for a while, but eventually did by the time the Lutz's moved?

Could that shotgun-ruined image have been a ghost of one of the slain members of the DeFeo family? If ghosts wander the way of the world due to tragic deaths, then the DeFeo family certainly qualified, as witnessed below.

The Defeo children when they were alive, clockwise starting from back row: John-Matthew, Alison, Marc, Dawn, and Ronnie (Butch).

CRIME SCENE PHOTOGRAPHS

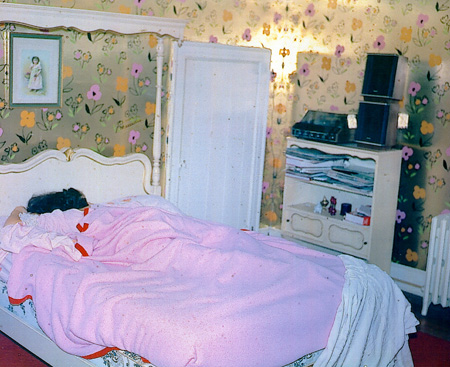

John DeFeo, aged 9:

Marc DeFeo, aged 12. The camera was not advanced properly for the first print, which explains the double image (no, not a ghost!). The wheelchair was needed at the time for a temporary sports injury.

Alison DeFeo, aged 13:

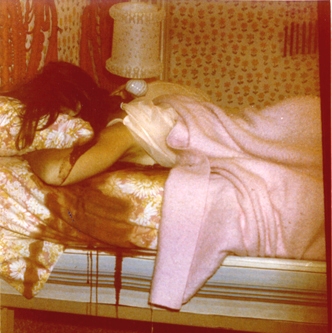

Dawn DeFeo, age 18:

The parents:

And who did these terrible murders? Ronnie (Butch) DeFeo has been convicted for these crimes:

THE MOVIE WAS INSPIRED BY A REAL MURDER

What really happened that night?

The DeFeos were a family of seven who lived in the upscale Amityville Village of New York's Long Island. One evening, around 6:30pm, the eldest son, Ronnie (Butch) DeFeo, ran into a local bar shouting that someone had killed his parents. A goup of bar patrons (many of whom were friends of Ronnie's) jumped into a car and zoomed down the few blocks to Ronnie's house, where they found not only the parents, but every member of Ronnie's family shot dead in their beds. The father was shot in the back and in the neck. The mother was shot twice in the upper body. Ronnie's two younger sisters were each shot once in the head at close range. His two younger brothers were each shot once in the back at close range.

Ronnie was taken to the police station for questioning and protection. While there, he quickly became the number one suspect, and confessed to police detectives that he did, in fact, commit the murders.

The members of his family:

Ronald DeFeo, 43 (1930-1974)

Louise DeFeo, 43 (1931-1974)

Dawn DeFeo, 18 (1956-1974)

Allison DeFeo, 13 (1961-1974)

Marc DeFeo, 12 (1962-1974)

John DeFeo, 9 (1965-1974)

Ronnie was tried the following year. Before the trial began, by the end of May, 1975, Ronnie had gone through three different lawyers -- the last one claiming that Ronnie had tried to assault him. Eventually, on July 7th, the judge assigned William Weber to act as Ronnie DeFeo's attorney. The trial began in September of 1975 and ended that November. Despite William Weber's strategy of going with an insanity defense, Ronnie was found guilty of all six murders. He is currently serving his prison sentence of 25 years to life at the Green Haven Correctional Facility in Stormville, New York.

It was another routine evening at the Suffolk County, NY, emergency dispatch switchboard. Calls had not been pouring in, and anyway, this placid New York City suburb scarcely had any crime to complain of, at least by City standards. Suddenly, at 6:35 p. m., the calm was destroyed by a phone call that would shatter the safe suburban aura that pervaded the county. Transcripts from the conversation demonstrate the caller's rattled composure as he tried to relate to an operator the horrifying scene he and his friends had been led to:

Operator:This is Suffolk County Police. May I help you?"

Man: "We have a shooting here. Uh, DeFeo."

Operator: "Sir, what is your name?"

Man: "Joey Yeswit."

Operator: "Can you spell that?"

Man: "Yeah. Y-E-S W I T."

Operator: "Y-E-S . .

Man: "Y-E-S-W-I-T."

Operator: ". . . W-I-T. Your phone number?"

Man: "I don't even know if it's here. There's, uh, I don't have a phone number here."

Operator: "Okay, where you calling from?"

Man: "It's in Amityville. Call up the Amityville Police, and it's right off, uh . . . Ocean Avenue in Amityville."

Operator: "Austin?"

Man: "Ocean Avenue. What the ... ?"

Operator: "Ocean ... Avenue? Offa where?"

Man: "It's right off Merrick Road. Ocean Avenue."

Operator: "Merrick Road. What's ... what's the problem, Sir?"

Man: "It's a shooting!"

Operator: "There's a shooting. Anybody hurt?"

Man: "Hah?"

Operator: "Anybody hurt?"

Man: "Yeah, it's uh, uh — everybody's dead."

Operator: "Whattaya mean, everybody's dead?"

Man: "I don't know what happened. Kid come running in the bar. He says everybody in the family was killed, and we came down here."

Operator: "Hold on a second, Sir."

(Police Officer now takes over call)

Police Officer: "Hello."

Man: "Hello."

Police Officer: "What's your name?"

Man: "My name is Joe Yeswit."

Police Officer: "George Edwards?"

Man: "Joe Yeswit."

Police Officer: "How do you spell it?"

Man: "What? I just ... How many times do I have to tell you? Y-E-S-W-I-T."

Police Officer: "Where're you at?"

Man: "I'm on Ocean Avenue.

Police Officer: "What number?"

Man: "I don't have a number here. There's no number on the phone. "

Police Officer: "What number on the house?"

Man: "I don't even know that."

Police Officer: "Where're you at? Ocean Avenue and what?"

Man: "In Amityville. Call up the Amityville Police and have someone come down here. They know the family."

Police Officer: "Amityville."

Man: "Yeah, Amityville."

Police Officer: "Okay. Now, tell me what's wrong."

Man: "I don't know. Guy come running in the bar. Guy come running in the bar and said there — his mother and father are shot. We ran down to his house and everybody in the house is shot. I don't know how long, you know. So, uh . . ."

Police Officer: "Uh, what's the add ... what's the address of the house?"

Man: "Uh, hold on. Let me go look up the number. All right. Hold on. One-twelve Ocean Avenue, Amityville."

Police Officer: "Is that Amityville or North Amityville?"

Man: "Amityville. Right on ... south of Merrick Road."

Police Officer: "Is it right in the village limits?"

Man: "It's in the village limits, yeah."

Police Officer: "Eh, okay, what's your phone number?"

Man: "I don't even have one. There's no number on the phone. "

Police Officer: "All right, where're you calling from? Public phone?"

Man: "No, I'm calling right from the house, because I don't see a number on the phone."

Police Officer: "You're at the house itself?"

Man: "Yeah."

Police Officer: "How many bodies are there?"

Man: "I think, uh, I don't know — uh, I think they said four."

Police Officer: "There's four?"

Man: "Yeah."

Police Officer: "All right, you stay right there at the house, and I'll call the Amityville Village P.D., and they'll come down."

By the end of the evening, police investigators would find an additional two bodies, bringing the Ocean Avenue death toll to six. Six of seven members of the Ronald DeFeo family had been methodically murdered as they slept in their beds, leaving Ronald DeFeo, Jr., as the sole survivor of the grisly suburban bloodbath.

Ronald DeFeo, Sr., had attained a trophy-size piece of the American dream when he purchased the house at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, Long Island. Having been born and raised in Brooklyn, Ronald had worked hard in his father-in-law's Brooklyn Buick dealership, and after many years began to reap rich benefits. Money was no longer a concern when he finally made the decision to leave the City and move to Long Island. The home he chose was a classic piece of Americana, two stories plus an attic, several rooms, and a boathouse on the Amityville River. There was plenty of room for him, his wife Louise; and five children. A signpost in the front yard read "High Hopes," a testament to what the new home had symbolized for the DeFeos.

But beneath the veneer of success and happiness, Ronald was a hot-tempered man, given to bouts of rage and violence. There were stormy fights between him and Louise, and he loomed before his children as a demanding authority figure. As the eldest child, Ronald, Jr., bore the brunt of his father's temper and expectations. As a young boy, Ronald, Jr., or Butch as he would come to be called, was overweight and sullen, the victim of schoolyard taunts and unpopular with other children. His father encouraged him to stick up for himself, but while his advice pertained to the treatment of schoolyard bullies, it apparently did not apply to how young Ronald was treated at home. Ronald, Sr., had no tolerance for backtalk and disobedience, keeping his eldest son on a short leash, and refusing to let him stand up for himself the way he was commanded to at school.

As Butch matured into adolescence, he gained in size and strength, and was no longer a sitting duck for his father's abuse. Shouting matches often degenerated into boxing matches, as father and son came to blows with little provocation. While Ronald, Sr. was not highly skilled in the art of interpersonal relations, he was astute enough to realize that his son's bouts of temper and violent behavior were highly irregular, even in relation to his own. He and his wife arranged for their son to visit a psychiatrist, but to no avail as Butch simply employed a passive-aggressive stance with his therapist, and rejected any notion that he himself needed help.

In the absence of any other solution, the DeFeos employed a time-honored strategy for placating unruly children: they started buying Butch anything he wanted and giving him money. At the age of 14, his father presented him with a $14,000 speedboat to cruise the Amityville River. Whenever Butch wanted money, all he had to do was ask, and if he wasn't in the mood to ask, he simply took it.

By the age of 17, Butch was forced to leave the parochial school he was attending. By this time he had begun using serious drugs such as heroin and LSD and had also started dabbling in petty thievery schemes. His violent behavior was becoming increasingly psychotic as well, and was not confined to outbursts within his home. One afternoon while out on a hunting trip with some friends, he pointed his loaded rifle at a member of their party, a young man he had known for years. He watched with a stony expression as the young man's face turned white. He fled, and Butch calmly lowered his gun. When they caught up with their friend later that afternoon, Butch asked him why he had left so soon.

At the age of 18, Butch was given a job at his grandfather's Buick dealership. By his own account it was a gravy job, where little was expected of him. Regardless of whether or not he showed up for work, he received a cash allowance from his father at the end of each week. This he used for his car (which his parents had also purchased), for alcohol, and for drugs such as speed and heroin. Altercations with his father were growing ever more frequent and correspondingly more violent. One evening, a fight broke out between Mr. and Mrs. DeFeo. In order to settle the matter, Butch grabbed a 12-gauge shotgun from his room, loaded a shell into the chamber, and charged downstairs to the scene of the altercation. Without hesitating or calling out to break up the fight, Butch pointed the barrel of the gun at his father's face, yelling, "Leave that woman alone. I'm going to kill you, you fat f***! This is it." Butch pulled the trigger, but the gun mysteriously did not go off. Ronald, Sr. froze in place and watched in grim amazement as his own son lowered the gun and simply walked out of the room with casual indifference to the fact that he had almost killed his father in cold blood. That fight was over, but Butch's actions foreshadowed the violence he would soon unleash not only upon his father, but his entire family.

Shots in the Night

In the weeks before the slayings, relations between Butch DeFeo and his father had reached the breaking point. Butch, apparently dissatisfied with the money he "earned" from his father, had devised a scheme to further defraud his family. Two weeks before the slayings, Butch was sent on an errand by one of the staff at the Buick dealership, given the responsibility of depositing $1,800 in cash and $20,000 in checks in the bank. Instead, Butch arranged to be "robbed" on his way to the bank by an acquaintance, with whom he later split the loot.

Butch and another accomplice from the dealership departed for the bank at 12:30. They did not return for two hours, and when they did, they reported that they had been robbed at gunpoint while they were waiting at a red light. Ronald Sr., was at the dealership when his son returned, and exploded with rage when he heard Butch's story, berating the staff member who had sent him in the first place. The police were called, and when they arrived they naturally asked to speak to Butch. However, instead of engaging in a charade of cooperation, instead of at least devising a basic description of the fictional bandit, Butch became tense and irritable with the police. He became outright violent as they began to suspect that he was lying, and their questions started to focus on the two hours he was away. Wouldn't he have hastened back to the Buick dealership once he had been robbed of so much money? Where had he been during that time? In response to their questions, Butch began to curse at them, banging on the hood of a car in his grandfather's lot to emphasize his rage. The police backed off for the moment, but Ronald, Sr. had already come to his own conclusion about the motive for his son's behavior.

On the Friday before the murders, Butch had been asked by the police to examine some mug shots in the possibility that he might be able to finger the thief. He initially agreed, but pulled out at the last minute. When Ronald, Sr. heard of this, he confronted his son at work, demanding to know why he wouldn't cooperate with the police. "You've got the devil on your back," his father screamed at his son. Butch didn't hesitate. "You fat prick, I'll kill you." He then ran to his car and sped off. This fight had not come to blows. But the final confrontation was imminent.

The still shroud of night blanketed the village of Amityville in the early morning hours of Thursday, November 14, 1974. Stray house pets and the odd car were the only signs of life as families and neighbors slumbered. But hatred and savagery were brewing beneath the seeming calm at 112 Ocean Boulevard. The entire DeFeo family had gone to bed, with the exception of Butch. As he sat in the quiet of his room, he knew what he wanted to do, what he in fact was going to do. His father and his family would be a nuisance to him no longer.

Butch was the only member of the family with his own room. His violent disposition and the fact that he was the eldest had afforded him this small luxury. It also afforded him a private storage place for a number of weapons he collected and sometimes sold. On the night of the murders, Butch selected a .35-caliber Marlin rifle from his closet, and set off, stealthily but resolutely, towards his parents' bedroom.

He quietly pushed aside the door to their room and momentarily observed them as they slept, unaware of the horror at the foot of their bed. Then, without hesitation, Butch raised the rifle to his shoulder and pulled the trigger, the first of 8 fatal shots he would fire that night. This first shot ripped into his father's back, tearing through his kidney and exiting through his chest. Butch fired another round, again hitting his father in the back. This shot pierced the base of Ronald, Sr.'s spine, and lodged in his neck.

Louise DeFeo, victim

By now, Louise DeFeo had roused herself, and had barely a few seconds to react before her son began to fire upon her. Butch aimed the weapon at his mother as she lay prone on her bed, and fired two shots into her body. The bullets shattered her rib cage and collapsed her right lung. Both bodies now lay silently in fresh pools of their own blood.

Despite the distinct snap of each rifle shot, no one else stirred in the house. Butch quickly surveyed the destruction he had wrought, before resuming his massacre of the innocent. His two young brothers, John and Mark, would be the next victims of Butch's murderous sense of self-righteousness and rage.

Mark & John Mathew DeFeo,

victims

He entered the bedroom the two boys shared and stood between their two beds. Standing directly above his two helpless brothers, Butch fired one shot into each of the boys as they lay sleeping. The bullets tore through their young bodies, ravaging their internal organs, laying waste to the lives that lay ahead of them. Mark lay motionless, while John, whose spinal cord had been severed by his brother's heartless attack, twitched spasmodically for a few moments after the shooting. Again, the shots had not roused the only remaining members of the DeFeo family, and Butch skulked unchallenged to the bedroom his sisters Dawn and Allison shared. Dawn was the closest in age to Butch, while Allison was in grade school with John and Mark.

Allison & Dawn DeFeo,

victims

As Butch entered the room, Allison stirred and looked up just as he lowered the rifle to her face and pulled the trigger. His youngest sister was murdered instantly. Butch aimed his weapon at Dawn's head as well, literally blowing the left side of her face off.

It was just after 3:00 a.m. In a span of less than fifteen minutes, Ronald "Butch" DeFeo, Jr., had brutally slain each defenseless member of his family in cold blood. The DeFeo's dog Shaggy was tied up out by the boathouse, and was barking violently in reaction to the brutality occurring in the house. His barking didn't distract Butch one bit, however. Aware that he had completed the task he had set out to do, he now turned his attention to cleaning himself up and establishing an alibi to throw the inevitable police investigation off the trail. Butch calmly showered, trimmed his beard, and dressed in his jeans and work boots. He then collected his bloodied clothing and the rifle, wrapped them up in a pillowcase, and headed out to his car. He threw the evidence into the car, and took off into the pre-dawn hours before sunrise. Butch drove from the suburbs into Brooklyn, and disposed of the pillowcase and its contents by casting them into a storm drain. He then returned to Long Island, and reported to work at his grandfather's Buick dealership, business as usual. It was 6:00 a.m.

Unmasking a Murderer

Ronald DeFeo, Jr.

Butch did not remain at work for long. He called home several times, and when his father failed to show up, he acted as though he were bored with nothing to do, and left around noon. He called his girlfriend, Sherry Klein, to let her know that he would be home early from work, and that he wanted to stop by and see her. On his way back into Amityville, Butch passed his friend, Bobby Kelske, and the two stopped to talk. Butch proceeded on to Sherry's house, arriving at about 1:30 p.m. Sherry was 19 years old, a shapely and popular waitress at one of the many bars Butch frequented with his friends. Upon arriving, Butch casually mentioned that he had tried to call home several times, and, although all the cars were in the driveway, there was no response. To demonstrate, he called home from Sherry's apartment with the same, predictable result.

Acting puzzled but unconcerned, Ronald took Sherry shopping during the afternoon. From the mall in Massapequa, they drove to Bobby's house. Ronald gave Bobby the same report he had given Sherry, that his family appeared to be home, but that there was no answer when he called on the phone. "There's something going on over there," he said. "The cars are all in the driveway and I still can't get in the house. I called the house twice and nobody answered." Abruptly shifting gears, Butch asked if Bobby was going out later. Bobby replied that he was going to take a nap, and that if Butch wanted to meet him out, he would be at a local bar called Henry's around 6:00.

Butch spent the remainder of the afternoon visiting friends, drinking, and taking heroin. He finally arrived at Henry's after 6, and Bobby followed him in shortly thereafter. Once again, Butch feigned concern over his inability to reach anyone at home. "I'm going to have to go home and break a window to get in," he told Bobby. "Well, do what you have to do," his friend replied blithely. Ronald exited the bar on his supposed journey of discovery, only to return within a few minutes in a state of agitation and dismay. "Bob, you gotta help me," he implored. "Someone shot my mother and father!"

The two friends were joined by a small group of patrons, and they all piled into Butch's car, with Bobby at the wheel. It had been approximately 15 hours since the murders took place. Within moments after arriving at the house, Bobby Kelske had entered the front door and raced upstairs into the master bedroom. There lay the bodies of Ronald, Sr., and his wife, Louise. He returned outside to find Butch beside himself with ostensible grief and dismay. Joey Yeswit had found the telephone in the kitchen, and was calling the police. Within ten minutes the first policeman was on the scene, Officer Kenneth Geguski. As he arrived, he found a group of men gathered on the DeFeo's front lawn. Butch was among them, sobbing uncontrollably. "My mother and father are dead," he said as Geguski approached the group.

The Village of Amityville patrolman entered the house and immediately went upstairs. He first discovered the bodies of Ronald and Louise, as well as those of John and Mark DeFeo. He returned downstairs to phone village headquarters from the kitchen. Ronald was seated at the kitchen table, still crying. As he listened to Geguski's description, he alerted the officer to the fact that he also had two sisters. Geguski put the receiver down and hurried back upstairs. By this time another village patrolman had arrived, officer Edwin Tyndall. The two of them found Dawn and Allison's room together. It would take a forensics investigator to locate where the girls had been shot, and what kind of gun had killed them: there was too much blood for the officers to even begin to guess.

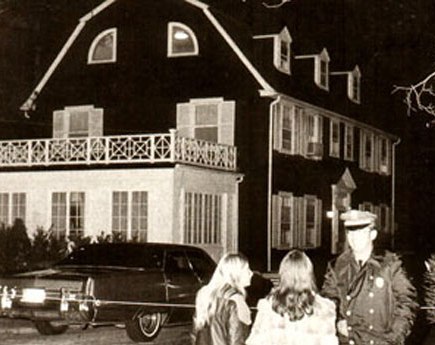

The DeFeo house with officers both

inside and outside

Shortly after 7:00 p.m., the neighborhood was buzzing with word of what had transpired in the house called High Hopes. The house itself was filled with police personnel, while neighbors and assorted gawkers gathered on the front lawn. Suffolk County detective Gaspar Randazzo was the first to question Butch, the massacre's sole survivor. They sat together in the DeFeo kitchen, as Randazzo asked Butch who he thought could have done such a thing. "Louis Falini," Butch replied after a moment's pause. Falini was a notorious mafia hit man whom Butch claimed held a grudge against his family as a result of an argument between the two of them a few years prior.

The interview continued at the next-door- neighbor's house, where a temporary police command center had been established. Detective Gerard Gozaloff joined in the process. It was suggested that, if the murders were indeed linked to organized crime, that Butch might still be a target, and that any further questioning should take place at police headquarters. It was here that they were joined by a third detective, Joseph Napolitano. And it was here that Butch gave police his written statement. In it, he claimed to have been home the night before, and that he stayed up until 2:00 a.m. watching the film Castle Keep on television. At 4:00 a.m., he reported walking past the upstairs bathroom, and that his brother's wheelchair was in front of the door. He also claimed to have heard the toilet flush. Since he couldn't go back to sleep, he decided to head to work early. He described the rest of his day, leaving work early, visiting with Sherry and Bobby, drinking, and trying to reach his family by telephone. He said that when he finally returned home to check on his family, he entered the house through a kitchen window, and went upstairs where he discovered his parents' bodies. Upon his discovery, he raced downstairs and back to Henry's Bar, where he rounded up some men who subsequently alerted the police.

After Butch submitted his signed statement, the detectives continued to question him about his family, about his suggestion that Louis Falini might be the killer. Butch replied that Falini had lived with them for a period of time, and during that time he had helped Butch and his father carve out a hiding space in the basement where Ronald, Sr., kept a stash of gems and cash. His argument with Falini had stemmed from an incident where Falini criticized some work Butch had done at the auto dealership. Butch also voluntarily confessed to being a casual user of heroin, as well as to the fact that he had set one of his father's boats on fire so that Ronald, Sr., could collect on an insurance claim rather than paying for the motor, which Butch had originally damaged. Around 3:00 a.m. the detectives had finished their questioning, and Butch went to sleep on a cot in a back filing room. Ronald, Jr., gave every appearance of a cooperative witness, and so far the detectives had no reason to hold Butch under suspicion.

That circumstance was beginning to change, however, as investigators continued to examine physical evidence, both at the crime scene and in the police laboratory. A crucial discovery was made around 2:30 a.m., November 15, when Detective John Shirvell was making a last sweep through the DeFeo bedrooms. Rooms where the murders had taken place had been scoured thoroughly, while Ronald's room had so far been given a cursory once-over. But, upon a second look, Det. Shirvell spotted a pair of rectangular cardboard boxes, both with labels describing their recent contents: Marlin rifles, a .22 and a .35. Shirvell was unaware that a .35-caliber Marlin had been the murder weapon, but snagged the boxes anyway in the event that they may be important evidence. Indeed they were! Shortly after arriving at police headquarters with the new evidence, Shirvell learned exactly what make of weapon had been used in the murders. Subsequent questioning of Bobby Kelske led to the discovery that Butch was a gun fanatic, and that he had staged the robbery of the Brigante Buick receipts.

In short order, the detectives on the case began to seriously consider the possibility that Butch had been playing them, that he may be their suspect, that he at least knew much more about the killings than what he had told them so far. At 8:45 a.m., Detective George Harrison shook Butch awake. "Did you find Falini yet?" DeFeo asked. But Harrison was not there with any such news: he was there to read Butch his rights. DeFeo protested that he had been trying to be cooperative all along, and that it wasn't necessary to read him his rights. He went so far as to waive his right to counsel, all to prove that he was an innocent witness with nothing to hide.

By this time, Gozaloff and Napolitano were exhausted. Two other officers, Lt. Robert Dunn and Detective Dennis Rafferty, took over. These two meant business. Rafferty re-read Butch his rights, and proceeded to question the suspect about his activities and whereabouts over the prior two days. Rafferty zeroed in on the time of the murders. Butch had written in his statement that he was up as early as 4:00 a.m., and that he heard his brother in the bathroom at that time. "Butch, the whole family was found in bed lying in their bedclothes," said Rafferty. That indicates to me that it didn't happen at like one o'clock in the afternoon after you had gone to work." Rafferty continued to press Butch until he was able to pry him away from his earlier version of when the crime took place, establishing that the crime actually took place between 2:00 and 4:00 a.m.

With this slight fissure, Butch's crudely constructed story began to crumble. Dunn and Rafferty hammered at the discrepancies between Butch's stated version of the events and what the physical evidence led police to believe actually happened. Butch was physically linked to the scene once the time of the murders was established. At first, Butch tried desperately to make the best out of a deteriorating situation, trying to lead the detectives to believe that while he had indeed been present in the home during the murders, he had only been in each bedroom after the murders had taken place. But the police weren't biting.

"Butch, it's incredible," said Rafferty. "It's almost unbelievable. Butch, we know we have a thirty-five-caliber gun box from your room. Every one of the victims has been shot with a thirty-five-caliber. And you've seen the whole thing. There has to be more to it. It's your gun that was used."

More desperate than ever, Butch continued to lie, even as his lies put him more squarely in the middle of the murders. He told his interrogators that at 3:30 a.m., Louis Falini woke him up and put a revolver to his head. Another man was present in the room, Butch said, but upon further questioning, he could not provide any kind of physical description for the police. According to Butch's new version of events, Falini and his companion led Butch from room to room, murdering each one of his family members. The police let Butch keep talking, and he eventually implicated himself as he described how he gathered and then discarded evidence from the crime scene. "Wait a minute," said Rafferty. "Why did you pick up the cartridge if you had nothing to do with it? You didn't know it was your gun that was used."

Butch didn't respond to the question, so the investigators allowed him to talk some more. They had already mined a good deal of evidence implicating Butch, all the while pretending to believe that Falini and his accomplice had taken Butch along on their killing spree while sparing his life alone. Once they had been given a solid description of how the murders took place, Dunn went in for the kill. "They must have made you a piece of it," he told Butch. "They must have made you shoot at least one of them — or some of them." Butch fell for it, and the trap was sprung.

"It didn't happen that way, did it?" asked Rafferty.

"Give me a minute," Butch replied, his head in his hands.

"Butch, they were never there, were they? Falini and the other guy were never there."

"No," Butch finally confessed. "It all started so fast. Once I started, I just couldn't stop. It went so fast."

The Trial

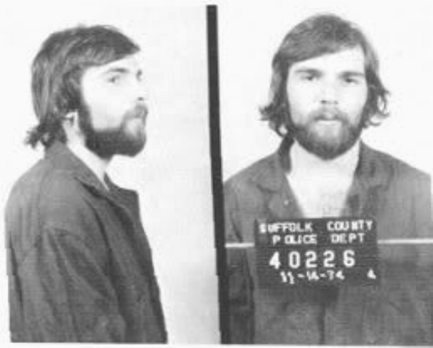

Ronald DeFeo mugshots

Butch DeFeo's case came to trial on Tuesday, October 14, 1975, almost one year after the murders took place. The prosecution of DeFeo, the responsibility to see to it that such a man would never be a danger to anyone in the community again, rested with Gerard Sullivan, assistant district attorney with Suffolk County, NY. Despite DeFeo's confession, despite the fact that he had been able to lead investigators to the exact spot where he had disposed of the evidence, and despite the fact that Butch's .35-caliber rifle was positively ID'd as the murder weapon, Sullivan took no chances in his approach to prosecuting. During the period of pre-trial interviews and jury selection, Sullivan had studied DeFeo, questioned him, observed how he behaved and interacted with others. He knew that Butch was a pathological liar, that he was evasive. He had retained well-known area attorney William Weber for his defense; his pattern of behavior before the murders would afford Weber the opportunity to plead innocence by reason of insanity on his client's behalf. But Sullivan knew that Butch DeFeo was not crazy, was indeed a violent, cold-blooded killer, and he was determined to put him away for good. His opening statement to the jury was crucial, as it would set the stage in his attempt to reveal the truth about DeFeo's criminal character. He could not afford to take for granted that the jury would see DeFeo as he did, as a sane, methodical murderer.

"Ladies and gentlemen of the jury," he said, "each of you will be changed to some degree by this case. You will leave this courtroom after rendering a verdict perhaps a month from now, carrying with you an abiding memory of the horror that occurred in that house at 112 Ocean Avenue in the dead of night eleven months ago."

"Bear in mind that the evidence establishing and bearing upon how these crimes were carried out is as important to your verdict as the proof bearing upon who carried them out," he continued, anticipating an insanity defense. "Much of the evidence of 'How?' will bear upon the issue of whether you will excuse the defendant for his action by reason of some mental disease or defect. If you will keep your minds open, carefully evaluate and assess all the proofs, I'm confident that at the end of the case you will come back into this courtroom and find Ronald DeFeo, Jr., guilty of six counts of murder in the second degree."

William Weber

The question of DeFeo's mental state at the time of the murders would remain the defining piece of evidence upon which his acquittal or conviction would rest. Prior to the trial, Weber had shrewdly attempted to have the case dismissed outright, alleging that Butch had been refused access to counsel right before the police took his confession. He further contended that the confession itself was obtained under duress, the product of physical abuse on the part of the police. Neither of these claims stood up under scrutiny, however, and Weber was left to defend his client's actions on the grounds that he was legally insane at the time they took place.

Sullivan was prescient enough to see that a one-dimensional argument that DeFeo was in fact sane and responsible for his actions might not be enough to convince the jury of his guilt. Sullivan called a number of witnesses, including police officers and detectives who had worked the case, and assorted relatives and friends of Butch's. Through their testimony, he sought to present to the jury a more three-dimensional portrait of the man who was capable of murdering six defenseless family members. But no witness offered him this opportunity more so than DeFeo himself.

Weber called his witness and led the questioning, predictably leading his client to supply responses that would burnish DeFeo's claim of insanity. Holding a picture of his mother as she lay slain in her bed, Weber asked his client, "Ronnie, that's your mother, isn't it?"

"No, Sir," Butch responded. "I told you before and I'll say it again. I never saw this person before in my life. I don't know who this person is."

Weber proceeded to show Butch a photo of his father's body, and asked, "Butch, did you kill your father?"

"Did I kill him? I killed them all. Yes, Sir. I killed them all in self-defense."

Sullivan wore his straightest poker face, while some members of the jury gasped out loud in response to DeFeo's courtroom confession. Weber continued unfazed, asking why Butch had done such a thing.

"As far as I'm concerned, if I didn't kill my family, they were going to kill me. And as far as I'm concerned, what I did was self-defense and there was nothing wrong with it. When I got a gun in my hand, there's no doubt in my mind who I am. I am God."

To the average layman member of the jury, DeFeo's testimony might have seemed to be that of a deranged lunatic, someone with a fleeting grasp on reality. And it was precisely this possibility, the possibility that DeFeo would escape judgment by duping the jury, that Sullivan worked the hardest to prevent. He wasted no time in assaulting DeFeo's testimony during cross-examination. He ridiculed Butch's seeming inability to remember who his own mother was, he exposed inconsistencies between his testimony and the statement he gave police on the night of the crime. Most of all, Sullivan pushed DeFeo's buttons, aggressively set forth to rattle his composure, to enflame his arrogance and hatred. Sullivan wanted the jury to see that, rather than the victim of insanity, Ronnie "Butch" DeFeo, Jr., was a lucid, devious, cold-blooded killer.

His questions began to center around the murders themselves, and DeFeo's conflicting accounts of his actions that night. Sullivan knew that he would not be able to get a straight accounting from Butch in regard to what had transpired, but he did know that he could goad the murderer into revealing the twisted sense of enjoyment he got from killing his entire family.

"You felt good at the time?" he asked.

"Yes, Sir. I believe it felt very good," Butch responded.

"Is that because you knew they were dead, because you had given them each two shots?"

"I don't know why. I can't answer that honestly."

"Do you remember being glad?"

"I don't remember being glad. I remember feeling very good. Good."

Sullivan's efforts to this end culminated in his provoking Butch to the point where he actually threatened the prosecutor's life. "You think I'm playing," he barked hatefully from the stand. "If I had any sense, which I don't, I'd come down there and kill you now."

The ability to prove or disprove DeFeo's mental state at the time of the killings was crucial to the success of both his defense and prosecution. Leaving nothing to chance, both sides had retained the services of two local, highly reputable psychiatrists. Dr. Daniel Schwartz was retained for the defense, and was no stranger to criminal proceedings. He had interviewed a number of defendants, testifying in hundreds of cases. He would later gain widespread national notoriety as the psychiatrist who found David Berkowitz to be criminally insane in the wake of the Son of Sam slayings.

Sullivan was aware of the crucial juncture the trial had now reached. All of the groundwork he had laid, all of his attempts to flesh out Butch DeFeo's murderous persona for the trial would be for naught if he were to allow Weber and Schwartz to take control of this final stage of the trial. Despite the fact that he had retained the services of another very prominent psychiatrist, Sullivan knew that he had to rely on his skills as a prosecutor and cross-examiner as on the abilities of his expert witness. As he wrote in his account of the trial, "The jurors had been learning about DeFeo and his murders for almost two months. They had listened to his lies and vituperation for days. Dr. Schwartz had only talked to him for hours. I would show that the psychiatrist didn't know the real Butch DeFeo."

As it happened, Sullivan caught a fortunate break in the form of Weber's questioning of his own witness. In a move that could clearly be interpreted as overconfidence in Schwartz's ability on the stand, Weber posed only a few preliminary questions to his witness, then proceeded to let Schwartz blithely deliver a mini-lecture on psychosis, disassociation, and criminal insanity. Sullivan noticed that the jury was indeed affected by his professional delivery, by what appeared to be his expert grasp of the subject and how it applied to Butch DeFeo's actions on the night of November 14, 1974. Despite this, Sullivan silently noted a number of key points Schwartz had made which Weber failed to challenge or ask Schwartz to expand upon. He smiled, silently planning to do so himself during cross.

Sullivan opened his line of questioning by referring to Schwartz's prior experience as an expert witness, attempting to rattle him by demonstrating the extent to which he had researched the witness. Seeing that this provided only limited benefit over a short period of time, Sullivan moved swiftly to the case at hand, contesting Schwartz's characterization of DeFeo's behavior after he had slain his family.

"Is this not indicative of a person who has gone to very careful lengths to remove evidence of the crime, that would connect him to that crime, out of that house?" Sullivan asked incredulously.

"It's evidence of somebody who is trying to remove evidence from himself, too, that he has done this," Schwartz responded. "We are now speculating as to the motive for the cleaning up. If you are familiar with Lady Mac Beth's complaint — 'What, will these hands never be clean?' — she's not hiding a murder from anyone, but she can't live with the imagined blood on her hands."

Sullivan didn't buy a word of it, and was determined not to let the jury buy it, either. "Doctor," he roared, "is that your considered psychiatric opinion?"

"My considered psychiatric opinion, Counselor, is that he's not hiding this crime from anybody by picking up the shells," Schwartz retorted hotly. "The bodies are there. The bullets are in the people."

"Everything that he could get that would connect him with the crime, he removed from the house, didn't he?" pressed Sullivan.

"What you are talking about is trivia compared to the six bodies," Schwartz responded flatly.

His indifferent response ignited the prosecutor's sense of outrage. "Trivia that he removed the evidence out of that house that would connect him to the crime, trivia that has nothing to do with whether he thought that the crime was wrong?" thundered Sullivan.

"The evidence is there in the victims," was Schwartz's only response. But Sullivan had him on the run, the respectability of his earlier testimony vanishing, receding in the face of the prosecutor's furious onslaught. Sullivan next took aim at Schwartz's actual diagnosis of DeFeo as a neurotic.

"So it's your testimony, as I understand it, Dr. Schwartz, that the fact that it wasn't too bright to throw everything in that sewer drain all together in one location is significant of the fact that it was neurotic that he did this?" Schwartz responded affirmatively, noting that DeFeo appeared to be acting without any clear purpose in mind, someone distracted by paranoid, neurotic delusions. In doing so, he fell straight into Sullivan's trap, a trap constructed with the very notes Schwartz had taken during his interview of Butch.

"Did he tell you about not wanting to leave clues for the police?" asked Sullivan. He indicated the passage in Schwartz's notes where DeFeo had made exactly such a statement.

"I asked him about the casings, and he said he didn't want to leave the police any clues as to what kind of gun it had been. He was not a friend of the cops, and he didn't want to help them."

The trap was sprung, Schwartz was now caught in his own testimony, and Sullivan stood triumphantly over his prey. "Okay, now you know why he removed the casings, don't you?" he asked derisively.

"I know one of the reasons. There are others," Schwartz responded angrily. But his testimony had been fatally wounded by Sullivan's aggressive questioning. "I have no further questions," the prosecutor announced as he strode back to his table.

Dr. Harold Zolan testified for the prosecution. Unlike Weber's style of questioning his expert witness, Sullivan devised an elaborate question-and-answer exchange with Zolan, making every deliberate effort to give the jury access to Zolan's thought process, so that they might come to understand how Zolan had reached his assessment, and that they might even reach the same assessment themselves. Unlike Schwartz, Zolan attributed DeFeo's behavior to an antisocial personality, a form of personality disorder he distinguished from any form of mental illness. Essentially, those with such a personality disorder are fully aware of their actions, are fully able to comprehend the difference between right and wrong, but are motivated by an imperious, self-centered attitude. Sullivan and his witness were thorough in their dissection of DeFeo, presenting an ironclad case to the jury in crystal-clear language that Butch was indeed responsible for his actions on the night of November 14, 1974. While Weber tried to rattle Zolan as Sullivan had rattled Schwartz, the prosecution's witness held fast to his diagnosis. Sullivan was confident that between his methodical questioning and Zolan's well-thought-out responses, the jury was finally in possession of clinical evidence that Butch was guilty of murder.

After each expert witness had been questioned and cross-examined, a few more witnesses were called by Sullivan to testify. While not central to his case, their additional testimony helped to bolster Sullivan's case against DeFeo. However, the verdict of innocence or guilt rested upon the question of DeFeo's sanity, as he knew it would. Weber and Sullivan made their summations. Then, on Wednesday, November 19, 1975, a year and five days since the murders, the presiding judge instructed the jury to gather in the deliberation chamber, and return to the court with a verdict for Ronald "Butch" DeFeo, Jr.

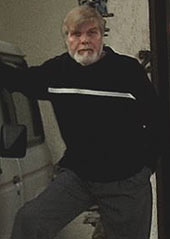

A more recent photo

of Ronald DeFeo

Despite Sullivan's painstaking efforts, he knew that a guilty verdict was not a sure bet. He was rewarded for his skepticism when the jury's first vote came back 10-2, with two holdouts who were still uncertain about DeFeo's mental state at the time of the murders. After reviewing transcripts of DeFeo's testimony, however, the vote came back at a unanimous 12-0. On Friday, November 21, 1975, Ronald DeFeo, Jr., was found guilty of six counts of second-degree murder. Two weeks later he was sentenced to twenty-five years to life in prison on all six counts. He remains incarcerated with the New York State Department of Corrections today.

Epilogue: Horror and Exploitation

The Amityville Horror book

"George and Kathy Lutz moved into 112 Ocean Avenue on December 18. Twenty-eight days later, they fled in terror." So begins Chapter One of Jay Anson's novel, The Amityville Horror. Written as a work of nonfiction, the book purports to relate the day-to-day events that drove the new residents of High Hopes from their home in terror. The book became a runaway bestseller, and was made into a popular movie starring Rod Steiger, Margot Kidder and James Brolin. "Their fantastic story, never before disclosed in full detail, makes for an unforgettable book with all the shocks and gripping suspense of The Exorcist, The Omen or Rosemary's Baby, but with one vital difference...the story is true," reads the trailer on the book's back cover.

The Side view of 112 Ocean Avenue

The one vital difference between truth and fiction is what paranormal investigator Dr. Stephen Kaplan spent many years trying to expose in regard to the Amityville "Horror." Now deceased, Dr. Kaplan was a well-respected Long Island parapsychologist. The founder of the Parapsychology Institute of America, he was a frequent guest on the WBAB radio program, "Spectrum with Joel Martin." On February 16, 1976, shortly after the Lutz family "fled" from the house on Ocean Avenue, Dr. Kaplan received a phone call from George Lutz, requesting that Dr. Kaplan and his associates investigate the house. As Dr. Kaplan recalled in his account of the incident, "The Amityville Horror Conspiracy", this initial conversation immediately began to arouse his suspicions as to the validity of George's claim that the house was haunted by demons and all variety of evil spirits.

"I began to ask questions. What actually happened to him and his family? George...says that he simply can't describe the psychic phenomena. But there are demons there. He even knows their names!

" 'What are their names?' I ask. [George] won't tell me. He claims they'll appear if he as much as mentions their names out loud.

" 'Who told you that?' I ask.

" 'I read it in a book.' I ask him for the title, but he can't remember — he's read so many books since they bought the house. Books on demonology, witchcraft, Satanism, ghosts, psychic phenomena — the list went on and on. And all in just a few short weeks, or so George claims.

"I press him about the demons and he answers by reciting 'facts' he has learned about demons and Satan worship. In a discussion about witchcraft, [George] mentions Ray Buckland, a prominent witch in the area who ran the Witchcraft Museum in Bayshore before moving to New England.

I am getting more suspicious by the minute. Didn't George just tell me that he knew nothing of the occult up until the past two months? Ray Buckland had been gone from New York for a year or two now. That would mean George had discussed 'the craft,' as it is called, with one of the most knowledgeable witches in the country long before he bought the house."

Dr. Kaplan's doubts about the veracity of the Lutz haunting were confirmed a year-and-a-half later, when he received a copy of The Amityville Horror. Reading it from cover to cover, he swiftly came to the conclusion that George had indeed done his witchcraft and demonology homework — the account was packed with every sort of ghost, ghoul, poltergeist, and demon, all of which employed every trick in the book to terrorize the Lutz family, but could not scare them into leaving for an entire month. The inconsistencies and fabrications Dr. Kaplan found include:

The complete exaggeration of the role a priest friend played in the whole drama. In the book, a priest character named Fr. Mancuso is terrorized by a demon while trying to bless the new home. He is then stalked by the specter back to the rectory, where he is afflicted with boils, bleeding palms (a la stigmata), a fever, and the pervasive scent of excrement. In real life, a priest did bless the house, and did have some concern about the possibility of a haunting. Both the real priest and rectory were unharmed by any such demon.

Henry's Bar, the scene of Butch's shocking revelation, is referred to as the "Witches Brew." An imaginary police sergeant named "Gionfriddo" mentions that the police discovered the murders because Butch told the bartender, a depiction of events that doesn't even come close to how they really occurred.

The supernatural phenomena that the Lutz's describe witnessing is too wide-ranging, which is to say that no one home could possibly hold enough demons, spooks, etc. to cause everything they say happened to them. For instance, George claims that a porcelain lion leapt from a corner of the living room and "bit" him on the ankle; George saw a ghostly vision of Ronnie DeFeo, Jr.'s head floating in the cellar; George and his wife Kathy believe they saw the burned impression of a demonic, hooded figure on their fireplace; Kathy levitated above their bed; Kathy looked in the mirror and saw a decrepit elderly woman looking back; the toilets backed up with black smelly ooze, and the walls of the house were covered with slime; George and Kathy looked out the living room window and saw a floating pig with glowing red eyes.

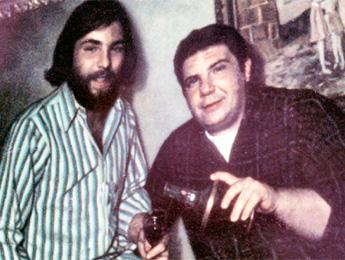

George & Kathy Lutz

In the end, this tale of horror and demonic possession was debunked by the Catholic Diocese of Rockville Center, the Amityville Police Department, William Weber (Butch DeFeo's defense attorney), U.S. District Court Judge Jack Weinstein, and even George and Kathy Lutz, who ended up recanting certain parts of the tale. The new owners of 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville were disturbed by no other visitors than the hordes of curious onlookers, and those convinced that theirs was a haunted house. This entire fabrication detracted from what was in fact the true horror of Amityville, the cold-blooded murder of six innocent people by one of their own family members.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.