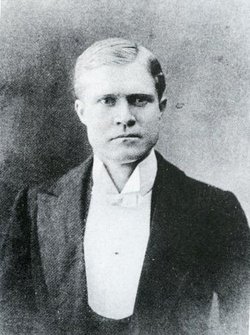

أوتا بونجا في عام 1904

Benga at the St. Louis World's Fair, 1904

من اكتر الحالات المُؤلمة هي حالة مواطن الكونغو " Ota Benga" والذى ولد سنة ١٨٨٣ وكان يعيش هو وزوجته وولديه كأي أُسرة سعيدة هادئة حتى يوم ما ذهب ليحضر طعام من خارج القرية ورجع ليجد اطفاله الإثنين وزوجته مقتولان وزوجته اُغتصبت قبل القتل، ولكى يزداد البلاء؛ أخذوه أسيرا كى يعرضوه على سمسار بشر ومُبشر امريكي شهير اسمه " سامويل فيليبس" كان عمله البحث عن أفارقة أقزام يشبهون القرود - من وجهة نظره وعلى حد وصفه العنصرى- وذلك لكى يعرضهم في معرض مُهتم بعلم ( تطور الأجناس) وبغرض إثبات نظرية داروين أن الإنسان أصله قرد وشراه بثمنٍ بخسٍ "ثمن كيس ملح"..

أوتا بونجا هو قزم من الكونغو (حوالي عام 1883 – 1916) تم تقديمه في المعرض الأنثروبولوجي في سانت لويس (ميزوري) 1904 بوصفه أقرب حلقة إنتقالية للإنسان، ولاحقا في معرض الإنسان المثير للجدل في حديقة الحيوان في برونكس عام 1906 حيث قام أحد الباحثين في مجال التطور بأسر أوتا بونجا سنة 1904 في الكونغو.

عام ١٩٠٤ وصل "Ota" لأمريكا وتم قصّ اسنانه عُنوة لتبدو مُدببة اسنانه وتم عرضه في معرض "برونكس" الدولي وكان عبارة عن ساحة محطوط فيها مجموعة قرود مُختلفة وهو جنبهم كإشارة انه التطور الطبيعي للقرود..

بعدها نقلوه لحديقة الحيوان في نفس قفص القرود وفي يوم الإفتتاح مدير الحديقة خطب في الناس " أنا سعيد لأني أملك هذا الشكل الإنتقالي الفريد في حديقتي".. "Ota" كان بيحكي ان اكتر حاجة آلمته هو الأطفال اللي كانوا بيرموا عليه الحجارة..

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), 09-30-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

معنى اسمه

يعني اسمه بلغته المحلية: الصديق.

حياته قبل اعتقاله

كان أوتا بونجا شاباً مرحاً يعيش مع زوجته وطفليه في قرية صغيرة محاطة بالغابات الإستوائية على ضفاف نهر كاساي في الكونغو التي كانت مستعمرة بلجيكية في ذلك الوقت (عام 1904). على الرغم من صعوبة حياة الأدغال البدائية، إلا أن أوتا بينغا كان شاباً (21 عاماً) مفعماً بالحيوية والإقبال على الحياة، ممارساً لدوره كزوج وأب

The Evening Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 09-25-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

اعتقال أوتا بونجا

في يومٍ مظلم، هجمت القوات الإستعمارية على قريته، وإبتدأ القتل العشوائي في أهل القرية البسطاء العـزّل، فأُبيدوا عن بكرة أبيهم! لم يبقى فيها شيء يتنفس، لكن أوتا بينغا نجى بسبب خروجه وقت الهجوم بحثاً عن الطعام، وعندما عاد هو ومَـن معه، كانت الفاجعة

شاهد أوتا بونجا زوجته وفلذتا كبده صرعى أمام عينيه وهو ليس بيده حولاً ولا قوة، واقتيد ومَن معه أسرى نحو حياةٍ من العبودية البائسة. كان حظ أوتا بونجا الأسوأ بين أقرانه، ذلك لانه في تلك الأيام كان قد وصل إلى أفريقيا المبشر والتاجر الأمريكي Samuel Phillips Verner قادماً بمهمة قبيحة مبالغ في انسلاخها عن كل ما هو آدمي

وهي أن يأتي بأقزام أفارقة يشبهون القرود، يتم عرضهم على الناس كإثبات على صحة نظرية داروين، وكان Samuel Phillips Verner مرسل لهذه المهمة بموجب عقد تجاري بينه وبين William John McGee وهو متخصص في علم الأعراق البشرية (علم يفلسف التطور العرقي للبشر على أساس نظرية داروين).

رأى صامويل في أوتا بونجا ضالته المنشودة، فقد كان بونجا قصير القامة لا يصل طوله إلى المتر ونصف. اقترب منه وفتح فمه ليرى أسنانه، ثم سأل، بكم هذا؟ ... وبعد أخذ وجذب اشتراه مقابل حفنة من الملح ملفوفة في خرقة بالية.

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), 09-24-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

أُجبر أوتا بونجا على مغادرة وطنه نحو المجهول رغماً عنه، وبضرب السياط ، حتى وصل إلى مدينة سانت لويس الأمريكية.

ظروف عيشه

قُيد أوتا بونجا بالسلاسل ووضع في قفص كالحيوان نُقل إلى اللمملكة المتحدة، بعد أن تم تدميـر قريتـه وقتل زوجته وولديـه وبعدها قام علماء التطور بعرضه على الجمهور في معرض سانت لويس العالمي إلى جانب أنواع أخرى من القردة، وقدموه بوصفه أقرب حلقة انتقالية للإنسان.

Charlotte Daily Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), 09-13-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

وبعد عامين نقلوه إلى حديقة حيوان برونْكس في نيويورك وعرضوه تحت مسمى السلف القديم للإنسان مع بضع أفراد من قردة الشمبانزي وبعض الغوريلات، وقام الدكتور التطوري ويليام هورناداي، مدير الحديقة، بإلقاء خطب طويلة عن مدى فخره بوجود هذا الشكل الانتقالي الفريد في حديقته وعامل أوتا بونجا المحبوس في القفص وكأنه حيوان عادي.

حياته كمواطن

في نهايةعام 1906،بمساعدة احد القساوسة تم اطلاق سراحه وعاش حياة طبيعية وأُطلق سراح بونجا تحت وصاية القس جيمس غوردون ووضع بينغا في ميتم هاورد للجوء السياسي للأيتام، وهو ملجأ تابع لكنسية تشرف عليه.

Samuel Phillips Verner

رتب القس غوردون في كانون الثاني 1910 لنقل بينغا إلى ايبسوم قرب لندن حيث عاش مع أسرة ماكاري، رتب الأمور لتسوية اسنان بينغا وأن يلبس نفس ملابس الأنكليز، وبذلك استطاع أن يكون جزءا من المجتمع المحلي. ، وحسّن لغته الإنجليزية، وبدأ بالذهاب إلى المدرسة الابتدائية في ايبسوم.

وبمجرد أن شعر أن لغته الإنجليزية تحسنت بما فيه الكفاية أوقف بينغا تعليمه الرسمي وبدأ العمل في مصنع للسجائر في ايبسوم. وعلى الرغم من حجمه الصغير، أثبت أنه موظف ثمين لأنه كان يستطيع أن يتسلق الأعمدة لإحضار ورق الدخان بدون ان يستخدم السلم. أسماه زملاءه في العمل بينغو. كان أحيانا يروي قصة حياته مقابل الساندويشات أو البيرة. وبدأ يخطط للعودة إلى أفريقيا.

انتحاره

William Temple Hornaday, the zoologist and founding director of Bronx Zoo, where Ota Benga was exhibited.

في عام 1914، عندما قرر الرجوع لبلده اندلعت الحرب العالمية الاولى، اصبحت العودة إلى الكونغو مستحيلة، فخاف ان يتعرض للأسر مُجددًا واكتئب بونجا لأن آماله بالعودة إلى الوطن خابت. وفي 20 آذار 1916 بعمر 32 سنة، أوقد ناراً احتفالية، ونزع الغطاء الذي وضع بأسنانه وأطلق النار على نفسه بالقلب بمسدس مسروق. ودفن في قبر غير معروف في مقبرة المدينة، قرب محسنه، غريغوري هيز.

أنتحر تاركًا رسالة مُؤلمة كتب فيها: " لا أستطيع تحمل وقوعي في الأسر مُجددًا.. كُنت اتمنى ان يُعاملني العالم باحترام.. فلتتذكروا هذا: انا لستُ قردًا، انا إنسان".

Richmond Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), March 22, 1916. From Early American Newspapers.

Ota Benga (c. 1883 – March 20, 1916) was an Mbuti (Congo pygmy) man, known for being featured in an anthropology exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904, and in a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo.

The Monkey House, New York Zoological Park, ca. 1910

Benga had been purchased from African slave traders by the missionary and anthropologist Samuel Phillips Verner, a businessman searching for African people for the exhibition. He traveled with Verner to the United States. At the Bronx Zoo, Benga had free run of the grounds before and after he was exhibited in the zoo's Monkey House. Except for a brief visit with Verner to Africa after the close of the St. Louis Fair, Benga lived in the United States, mostly in Virginia, for the rest of his life.

African-American newspapers around the nation published editorials strongly opposing Benga's treatment. Robert Stuart MacArthur, spokesman for a delegation of black churches, petitioned New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. for his release from the Bronx Zoo.

In late 1906, the mayor released Benga to the custody of James M. Gordon, who supervised the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. In 1910, Gordon arranged for Benga to be cared for in Virginia, where he paid for him to acquire American clothes and to have his teeth capped, so the young man could be more readily accepted in local society.

Printed in “Popular official guide to the New York Zoological Park,” by William T. Hornaday, 17th edition, June 1922

Benga was tutored in English and began to work at a Lynchburg tobacco factory. He proved a valuable employee because he could climb up the poles to get the tobacco leaves without having to use a ladder. He began to plan a return to Africa, but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 stopped ship passenger travel. Benga fell into a depression, and he committed suicide in 1916.

Early life

As a member of the Mbuti people, Ota Benga lived in equatorial forests near the Kasai River in what was then the Congo Free State. His people were attacked by the Force Publique, established by King Leopold II of Belgium as a militia to control the natives for labor in order to exploit the large supply of rubber in the Congo.

Detail from the Colorado Springs Gazette (Colorado Springs, Colorado), 10-14-1906. From Early American Newspapers

Benga's wife and two children were murdered; he survived only because he was on a hunting expedition when the Force Publique attacked his village. He was later captured by "Baschelel" (Bashilele) slave traders.

American businessman and explorer Samuel Phillips Verner travelled to Africa in 1904 under contract from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World Fair) to bring back an assortment of pygmies to be part of an exhibition. To demonstrate the fledgling discipline of anthropology, the noted scientist W. J. McGee intended to display "representatives of all the world's peoples, ranging from smallest pygmies to the most gigantic peoples, from the darkest blacks to the dominant whites" to show what was commonly thought then to be a sort of cultural evolution.

Olympia Daily Recorder (Olympia, Washington), 11-17-1904. From Early American Newspapers

Verner discovered Ota Benga while 'en route' to a Batwa village visited previously; he negotiated Benga's release from the slave traders for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. Verner later claimed Benga was rescued from the cannibals by him. The two spent several weeks together before reaching the village.

The Evening Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 03-06-1907. From Early American Newspapers.

There the villagers had developed distrust for the muzungu (white man) due to the abuses of King Leopold's forces. Verner was unable to recruit any villagers to join him until Benga spoke of the muzungu saving his life, the bond that had grown between them, and his own curiosity about the world Verner came from. Four Batwa, all male, ultimately accompanied them.

The Boston Journal (Boston, Massachusetts), 08-12-1904. From Early American Newspapers

Verner recruited other Africans who were not pygmies: five men from the Bakuba, including the son of King Ndombe, ruler of the Bakuba, and other related peoples – "Red Africans" as they were collectively labeled by contemporary anthropologists.

As exhibit

St. Louis World Fair

Benga (second from left) and the Batwa in St. Louis

The group was brought to St. Louis, Missouri, in late June 1904 without Verner, who had been taken ill with malaria. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition had already begun, and the Africans immediately became the center of attention. Ota Benga was particularly popular, and his name was reported variously by the press as Artiba, Autobank, Ota Bang, and Otabenga. He had an amiable personality, and visitors were eager to see his teeth, which had been filed to sharp points in his early youth as ritual decoration.

The Evening News (San Jose, California), 06-30-1904. From Early American Newspapers.

The Africans learned to charge for photographs and performances. One newspaper account, promoting Ota Benga as "the only genuine African cannibal in America", claimed "[his teeth were] worth the five cents he charges for showing them to visitors".

When Verner arrived a month later, he realized the pygmies were more prisoners than performers. Their attempts to congregate peacefully in the forest on Sundays were thwarted by the crowds' fascination with them. McGee's attempts to present a "serious" scientific exhibit were also overturned. On July 28, the Africans' performing to the crowd's preconceived notion that they were "savages" resulted in the First Illinois Regiment being called in to control the mob.

Detail of the Belgian Congo, with the Kasai River running vertically left of center. [Study Mission to Africa, September 1st to December 10th, 1955.] September 1, 1955. From the U.S. Congressional Serial Set

Benga and the other Africans eventually performed in a warlike fashion, imitating American Indians they saw at the Exhibition. The Apache chief Geronimo (featured as "The Human Tyger" – with special dispensation from the Department of War) grew to admire Benga, and gave him one of his arrowheads. For his efforts, Verner was awarded the gold medal in anthropology at the close of the Exposition.

American Museum of Natural History

Benga accompanied Verner when he returned the other Africans to the Congo. He briefly lived amongst the Batwa while continuing to accompany Verner on his African adventures. He married a Batwa woman who later died of snakebite, and little is known of this second marriage. Not feeling that he belonged with the Batwa, Benga chose to return with Verner to the United States.

Verner eventually arranged for Benga to stay in a spare room at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City while he was tending to other business. Verner negotiated with the curator Henry Bumpus over the presentation of his acquisitions from Africa and potential employment.

The Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 02-04-1904. From Early American Newspapers

While Bumpus was put off by Verner's request of the prohibitively high salary of $175 a month and was not impressed with the man's credentials, he was interested in Benga. Wearing a Southern-style linen suit to entertain visitors, Benga initially enjoyed his time at the museum. He became homesick, however.

The writers Bradford and Blume imagined his feelings:

What at first held his attention now made him want to flee. It was maddening to be inside – to be swallowed whole – so long. He had an image of himself, stuffed, behind glass, but somehow still alive, crouching over a fake campfire, feeding meat to a lifeless child. Museum silence became a source of torment, a kind of noise; he needed birdsong, breezes, trees.

The disaffected Benga attempted to find relief by exploiting his employers' presentation of him as a 'savage'. He tried to slip past the guards as a large crowd was leaving the premises; when asked on one occasion to seat a wealthy donor's wife, he pretended to misunderstand, instead hurling the chair across the room, just missing the woman's head. Meanwhile, Verner was struggling financially and had made little progress in his negotiations with the museum. He soon found another home for Benga.

Bronx Zoo

At the suggestion of Bumpus, Verner took Benga to the Bronx Zoo in 1906. William Hornaday, director of the zoo, initially hired Benga to use as help in maintaining the animal habitats. However, Hornaday saw that people took more notice of Benga than the animals at the zoo, eventually making Hornaday create an exhibition to feature Benga.

The Tucson Citizen (Tucson, Arizona), 09-20-1904. From Early American Newspapers

There, the Mbuti man was allowed to roam the grounds freely. He became fond of an orangutan named Dohong, "the presiding genius of the Monkey House", who had been taught to perform tricks and imitate human behavior. The events leading to his "exhibition" alongside Dohong were gradual: Benga spent some of his time in the Monkey House exhibit, and the zoo encouraged him to hang his hammock there, and to shoot his bow and arrow at a target. On the first day of the exhibit, September 8, 1906, visitors found Benga in the Monkey House. Soon, a sign on the exhibit read:

Mbye Otabenga, popularly known as “Ota Benga,”with the orangutan Dohong in the New York Zoological Gardens, 1906. Source: Library of Congress.

The African Pygmy, "Ota Benga."

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight, 103 pounds. Brought from the

Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Cen-

tral Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Ex-

hibited each afternoon during September.

Ota Benga at the Bronx Zoo in 1906. Only five promotional photos exist of Benga's time here, none of them in the "Monkey House"; cameras were not allowed.

Hornaday considered the exhibit a valuable spectacle for visitors; he was supported by Madison Grant, Secretary of the New York Zoological Society, who lobbied to put Ota Benga on display alongside apes at the Bronx Zoo. A decade later, Grant became prominent nationally as a racial anthropologist and eugenicist.

Reverend James Gordon led the protests against Ota Benga’s exhibition and captivity in the monkey house.

African-American clergymen immediately protested to zoo officials about the exhibit. Said James H. Gordon,

Kalamazoo Gazette (Kalamazoo, Michigan), 10-07-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes ... We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls." Gordon thought the exhibit was hostile to Christianity and a promotion of Darwinism: "The Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted.

A number of clergymen backed Gordon.

In defense of the depiction of Benga as a lesser human, an editorial in The New York Times suggested:

We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter ... It is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation Benga is suffering. The pygmies ... are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place ... from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.

Samuel P Verner took Benga captive in Congo and brought him back to the United States.

After the controversy, Benga was allowed to roam the grounds of the zoo. In response to the situation, as well as verbal and physical prods from the crowds, he became more mischievous and somewhat violent. Around this time, an article in The New York Times stated, "It is too bad that there is not some society like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and then we bring one here to brutalize him."

Samuel P Verner with two boys from the Batetela tribe in Congo in 1902

The zoo finally removed Benga from the grounds. Verner was unsuccessful in his continued search for employment, but he occasionally spoke to Benga. The two had agreed that it was in Benga's best interests to remain in the United States despite the unwelcome spotlight at the zoo. Toward the end of 1906, Benga was released into Reverend Gordon's custody.

Later life

Charlotte Daily Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), 10-02-1906. From Early American Newspapers

Gordon placed Benga in the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, a church-sponsored orphanage which he supervised. As the unwelcome press attention continued, in January 1910, Gordon arranged for Benga's relocation to Lynchburg, Virginia, where he lived with the McCray family. So that Benga could more easily be part of local society, Gordon arranged for the African's teeth to be capped and bought him American-style clothes. Tutored by Lynchburg poet Anne Spencer, Benga could improve his English, and he began to attend elementary school at the Baptist Seminary in Lynchburg.

Samuel Phillips Verner (center) with random Africans he bought at the behest of Louisiana Purchase Exposition and passed off as "pygmies" at World's Fair.

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), 10-06-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

Once he felt his English had improved sufficiently, Benga discontinued his formal education. He began working at a Lynchburg tobacco factory. He proved a valuable employee because he could climb up the poles to get the tobacco leaves without having to use a ladder. His fellow workers called him "Bingo". He often told his life story in exchange for sandwiches and root beer. He began to plan a return to Africa.

In 1914 when World War I broke out, a return to the Congo became impossible as passenger ship traffic ended. Benga became depressed as his hopes for a return to his homeland faded. On March 20, 1916, at the age of 32, he built a ceremonial fire, chipped off the caps on his teeth, and shot himself in the heart with a stolen pistol.

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), 09-26-1906. From Early American Newspapers.

He was buried in an unmarked grave in the black section of the Old City Cemetery, near his benefactor, Gregory Hayes. At some point, the remains of both men went missing. Local oral history indicates that Hayes and Ota Benga were eventually moved from the Old Cemetery to White Rock Cemetery, a burial ground that later fell into disrepair.

Legacy

“Pioneering in Central Africa,” by Samuel Phillips Verner. Richmond, Virginia: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903

Phillips Verner Bradford, the grandson of Samuel Phillips Verner, wrote a book on the Mbuti man, entitled Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (1992). During his research for the book, Bradford visited the American Museum of Natural History, which holds a life mask and body cast of Ota Benga. The display is still labeled "Pygmy", rather than indicating Benga's name, despite objections beginning a century ago from Verner and repeated by others. Publication of Bradford's book in 1992 inspired widespread interest in Ota Benga's story and stimulated creation of many other works, both fictional and non-fiction, such as:

1994 – John Strand's play, Ota Benga, was produced by the Signature Theater in Arlington, Virginia.

1997 – The play, Ota Benga, Elegy for the Elephant, by Dr. Ben B. Halm, was staged at Fairfield University in Connecticut.

2002 – The Mbuti man was the subject of the short documentary, Ota Benga: A Pygmy in America, directed by Brazilian Alfeu França. He incorporated original movies recorded by Verner in the early 20th century.

2005 – A fictionalized account of his life portrayed in the film Man to Man, starring Joseph Fiennes, Kristin Scott Thomas.

2006 – The Brooklyn-based band Piñataland released a song titled "Ota Benga's Name" on their album Songs from the Forgotten Future Volume 1, which tells the story of Ota Benga.

2006 – The fantasy film The Fall features a highly fictionalized character based on Ota Benga.

2007 – McCray's early poems about Benga were adapted as a performance piece; the work debuted at the Columbia Museum of Art in 2007, with McCray as narrator and original music by Kevin Simmonds.

2008 – Benga inspired the character of Ngunda Oti in the film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

2010 – The story of Ota Benga was the inspiration for a concept album by the St. Louis musical ensemble May Day Orchestra

2011 – Italian band Mamuthones recorded the song "Ota Benga" in their album Mamuthones.

2012 – Ota Benga Under My Mother's Roof, a poetry collection, was published by Carrie Allen McCray, whose family had taken care of Benga

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), 10-02-1906. From Early American Newspapers

2012 – Ota Benga was mentioned in the song, "Behind My Painted Smile", by English rapper Akala

2012 – Ota Benga the Documentary Film appeared (http://www.otabengathedocumentaryfilm.com/).

2015 – Journalist Pamela Newkirk published the biography Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga

2016 – Radio Diaries, a Peabody Award-winning radio show, tells the story of Ota Benga in "The Man in the Zoo" on the Radio Diaries podcast.

Similar case

Like Ota Benga, Ishi (a Native American) was displayed in the human zoo.

Similarities have been observed between the treatment of Ota Benga and Ishi. The latter was the sole remaining member of the Yahi Native American tribe, and he was displayed in California around the same period. Ishi died on March 25, 1916, five days after Ota.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.